This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered twice a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back to Moral Money.

Bond investors are grappling this week with Donald Trump’s extraordinary battle for influence over the Federal Reserve. Their counterparts in the clean energy space, meanwhile, are digesting a new escalation in the US government’s crackdown on the wind sector, which has already had a chilling effect on renewable power investment. As green investors look for other options, does Europe stand to gain?

US green energy upheaval creates an opportunity across the Atlantic

Say what you will about Donald Trump’s erratic policy positions, he’s been remarkably consistent for nearly two decades in his public antipathy towards wind power.

The US president has been loudly criticising the sector since 2006, when he bought a strip of coastal land in Scotland to build a golf course, a few miles from a site where an offshore wind farm was in the works.

In his first term, even as he continued to rail against “ugly” wind farms — and suggested they may cause cancer — Trump held back from government action against the sector, which actually enjoyed significant investment growth during that period.

The second term has been dramatically different. On his first day in office, Trump signed an executive order imposing an indefinite ban on new approvals for wind farms. His “big, beautiful bill” legislation then greatly shortened the period for which wind projects would be eligible for tax credits under Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

But the past few days have highlighted a still larger threat to this sector’s prospects in the US: the use of executive powers to strike down projects that have already received key permits and approvals, even if their development is well under way.

Shares in Denmark’s Ørsted fell 16 per cent to a record low on Monday, after a stop-work order on its $1.5bn wind project off the New England coast, which is already four-fifths complete. The order, from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, cited unspecified “concerns related to the protection of national security interests”.

The move comes as Trump puts pressure on Denmark over his desire to take possession of Greenland. But it is far from an isolated case.

Last Friday, the interior department said it intended to cancel federal approval for a wind farm off the coast of Maryland. That project is being pursued through a joint venture between Apollo Global Management and Italy’s Toto Holding.

Earlier this month, the government revoked approval for a wind farm in Idaho, citing “legal deficiencies in the issuance of the approval”.

In April, interior secretary Doug Burgum ordered Norway’s Equinor to halt construction of a $5bn wind project off the coast of New York. (That order was lifted after Trump and New York governor Kathy Hochul met to discuss a gas pipeline that had previously been blocked by the state’s regulators, and which now looks set to be revived.)

The moves make clear that there’s a danger for all companies developing wind farms in the US, especially but not exclusively offshore ones. These include Spain’s Iberdrola, which has several US offshore wind projects at various stages of development.

Small wonder, then, that Iberdrola has been on a US charm offensive, using the type of big-number investment pledges that have endeared the likes of SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son to the Trump administration. A few months ago, its executive chair Ignacio Galán met energy secretary Chris Wright and Burgum, stressing Iberdrola’s cumulative $50bn of investment in the US and plans to invest a further $20bn.

But other wind power developers have decided to cut their losses and run. Germany’s RWE said in April that it had halted work on projects in the US, where it holds three offshore leases, “given the political developments”. In the same month, Japan’s Mitsubishi abandoned plans for a floating wind farm off the coast of Maine. TotalEnergies and Shell have also dropped planned investments in US wind energy since Trump’s re-election.

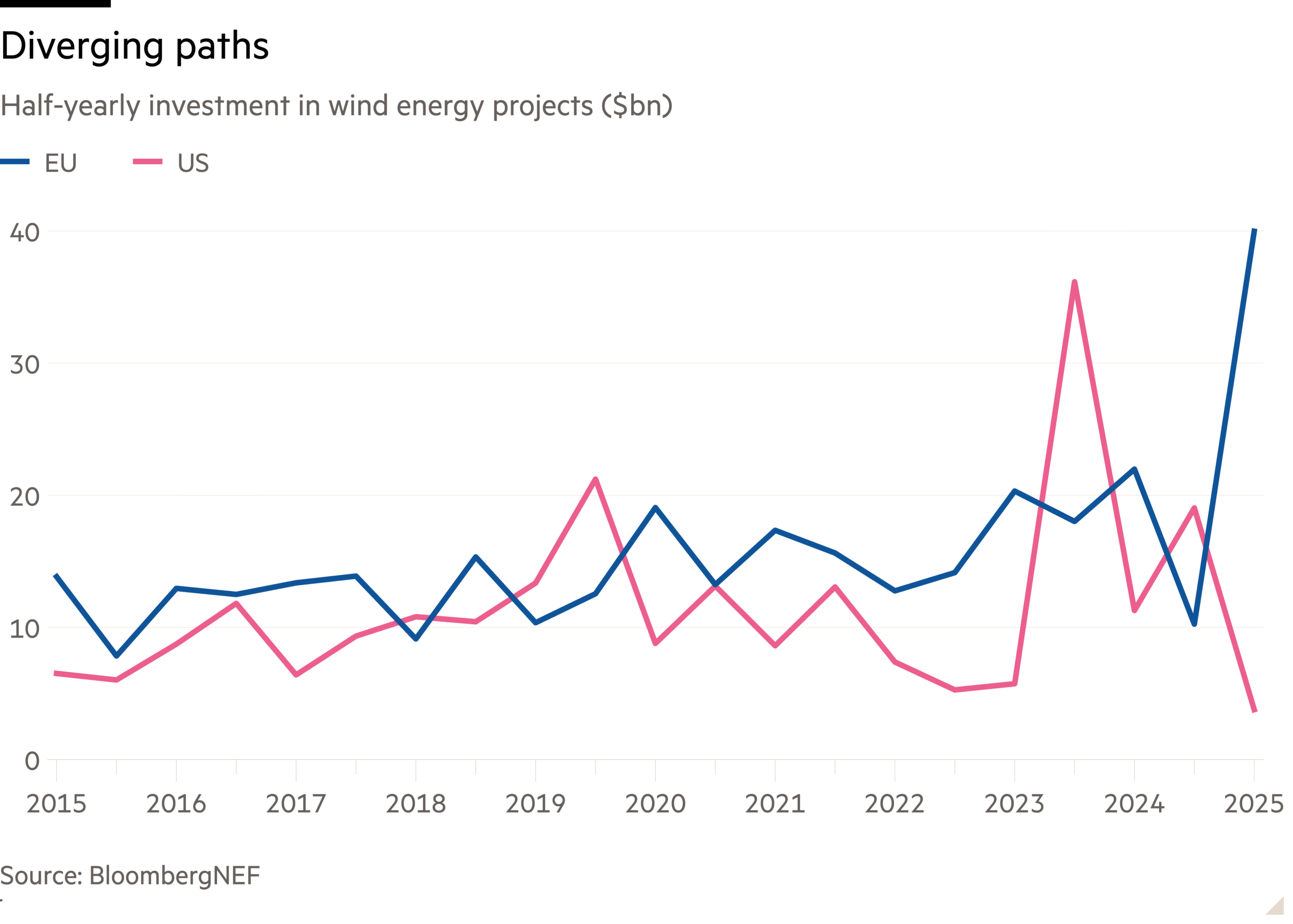

In the first half of this year, just $3.8bn was invested in US wind power projects — the lowest half-yearly figure since 2014 — and nothing at all in offshore ones, according to data published yesterday by research company BloombergNEF.

It would be wrong to attribute the investment squeeze solely to Trump. Higher interest rates have had a painful impact on renewable energy companies, which tend to take on large debt loads to fund their initial construction costs. Rising costs of key inputs, such as steel and copper, have also hurt.

But the latest investment data shows an undeniable Trump effect — and signs that Europe could be benefiting. Overall, US investment in solar and wind projects amounted to $35bn, down 36 per cent from the second half of last year. Investment in the EU was $75bn, a 63 per cent rise that indicates “developers and investors may be reallocating capital out of the US and into Europe”, BloombergNEF suggested. The EU growth was particularly strong in wind energy investment, which hit a record of $40bn, with a further $5.1bn in the UK.

The European renewable power sector has plenty of problems of its own — notably grid and storage constraints that mean renewable power producers are grappling with widespread negative pricing, as I wrote recently. But European governments are publicly prioritising policy reforms to support this sector’s growth, as they try to reduce reliance on Russian gas. For all the shortcomings of Europe’s renewable energy policy environment, the contrast with the situation in the US makes it look like a relative haven for developers and investors in this field.

Smart reads

Club in crisis The Net-Zero Banking Alliance has “paused” its activities after an exodus of US and European members. HSBC, Barclays and UBS all recently left the group, which was launched in 2021.

Money talks Global advertising company Interpublic, owner of agencies such as McCann, made a pledge to avoid contracts promoting fossil fuels. It didn’t last long . . .

Seller’s market China’s dominance in rare earth minerals gives it huge sway over Europe’s green energy transition, warns Gideon Rachman.

Damage control Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has sold its shares in Caterpillar, after its advisers alleged that Israel was using the US construction equipment maker’s products to commit “violations of international humanitarian law” by destroying Palestinian property.