Taqwa Ahmed Al-Wawi is a 19-year-old writer and poet from Gaza. She is currently a second-year English literature student at the Islamic University of Gaza.

The first bombs of the current genocide fell during Tasneem’s final weeks of pregnancy. When Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, she was 25 years old, seven months pregnant, and eagerly awaiting her third child.

In Gaza, Tasneem had already lived her whole young life under Israeli surveillance, confinement, and violence. But as the bombs rained down on October 7 — in what Israel claimed was retaliation for the nearly 1,200 Israelis killed that day, but has since become a two-year-long genocide, killing at least 66,000 Palestinians — it was clear her child’s generation would be born into a new level of horror.

There were no calm nurses by the time Tasneem went into labor with her son, Ezz Aldin. The hospital was overcrowded with no steady electricity. Tasneem labored for hours in the barely functioning hospital, and when she gave birth, there was no food to help her recover. Diapers were nearly impossible to find. Weakened and hungry, she breastfed her son. It was December 25, 2023.

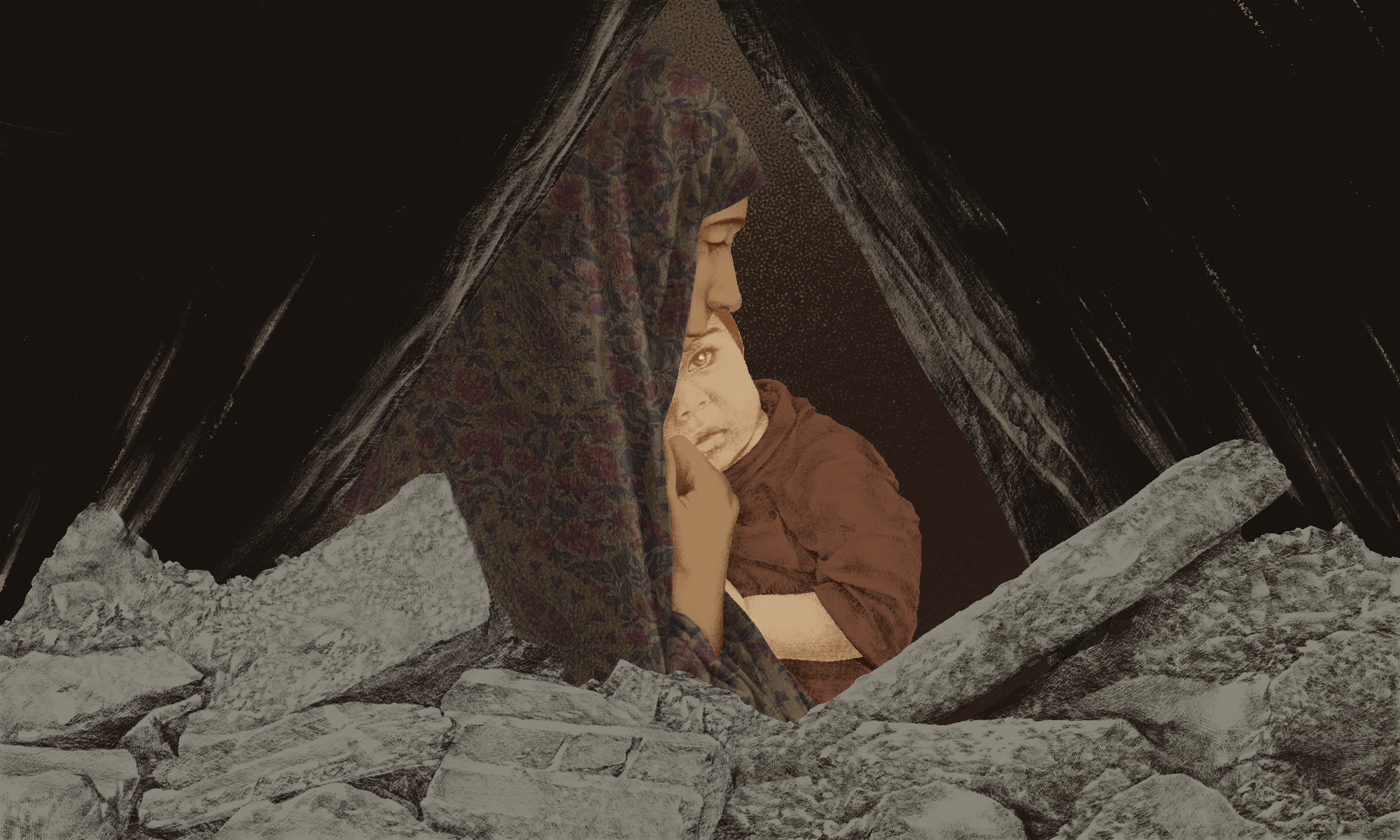

Bombs are still falling on Gaza, despite a pending peace deal. As the Israeli government, led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, moves into its third year of trying to ethnically cleanse Gaza, many Palestinian women still push to bring the next generation into the world. They give birth not in hospitals with clean beds and available staff, but in overcrowded, collapsing clinics, under drones and bombs, amid the deadliest genocide Gaza has seen in decades.

This is the story of my sisters, and of other Palestinian women who brought children into a world that was falling apart.

Doaa wasn’t pregnant when the first bombs dropped. Like everyone else, she was trying to survive. When her home was bombed on January 14, 2024, the windows shattered, the walls cracked, and the air was filled with smoke and dust. Though she wasn’t physically harmed, the emotional toll was enormous. A few weeks later, amid her family’s displacement — from a small flat, to a tent, to a tiny apartment — she found out she was pregnant. Living with a child growing inside her, under constant fear of sudden death, the sounds of nearby strikes would jolt her awake at night.

When her labor began — on October 28, 2024, just over a year into the genocide — she was rushed to an already overwhelmed hospital. She clung to the thin mattress through waves of pain, until her son Hossam was born: small, fragile, but alive. No special food awaited her. No clothes. No comfort. Still, she held him close, nursing him through hunger and fear.

The World Health Organization reports that 10 percent of Gaza’s population and up to 20 percent of pregnant women suffer moderate to severe malnutrition. Over 5,100 children were admitted to malnutrition programs in July alone, including 800 in critical condition. According to Médecins Sans Frontières, 25 percent of pregnant and breastfeeding women are malnourished. Mothers face shortages of nutritious food essential for recovery and breastfeeding, as iron-rich foods, fresh fruit, and vegetables are nearly impossible to find.

“What have these children done to deserve being born in these conditions of genocide and famine? Why can the world not see them?” asked my friend’s aunt, who gave birth on October 6, 2024. A single pack of diapers cost $600 at the time. Today, it’s 400 shekels, or about $120 — still impossibly out of reach. Most have to make do with a plastic bag tied up with string.

Her baby, Layan, had to drink formula. Many babies born in Gaza under the genocide do. Their mothers — starving, dehydrated, terrified — can’t make breast milk. When formula is available, it’s at inflated prices: 200 shekels per can. Most of the time, it simply isn’t there.

“What have these children done to deserve being born in these conditions of genocide and famine?”

Layan is now a year old. From the age of nine months, children are supposed to start eating soft food: mashed rice, boiled zucchini, fruit, grapes, melon, yogurt. But there’s nothing. Nothing to feed him. Nothing to grow on.

Dana was born in a tent by the sea, to a mother suffering from severe malnutrition. The family had been forced to leave their home in Khan Younis, and Dana’s mother had gone days without proper food.

“They told her mother she might give birth to a child with disabilities because of her lack of vitamins,” said Aya, Dana’s cousin.

The pregnancy was grueling. “I could barely get out of bed; there was hardly any food,” Dana’s mother recalled. Every day was a struggle against fatigue, hunger, and uncertainty. Her body weak, her mind anxious, she carried on, driven by hope for her baby. And against all odds, Dana arrived healthy — a small miracle in a world that seemed to offer none.

But the tents where displaced Palestinians reside are not fit places for children. Flies, mosquitoes, rats; the insects bite, sting, infect. A mosquito bite on a baby’s cheek swells for a week. Medical care is nearly impossible to find.

And the sewage system? A two-meter-deep pit in the ground, uncovered. There have been cases of children falling in.

In the heat, small bodies burn with fever. Skin diseases — itching, peeling, red blotches that blister — spread quickly. There are no creams. No medicine. Their immune systems are too weak to fight anything off.

“We had nothing but each other,” Dana’s mother said. Relatives, neighbors, and small acts of kindness became their lifeline, helping them prepare for the birth and supporting them through the first fragile days.

Now, Dana is thriving. But some babies don’t survive the winter. The tents freeze, and so do they.

As Noor rushed to the hospital in labor, her family’s car jolted violently from a nearby explosion. Her husband’s voice cracked as he called for calm, but the fear was thick in the air. The ambulance had been delayed, so they drove themselves through streets scattered with debris and silence broken only by distant blasts. Upon arriving, the hospital was overwhelmed — hallways packed with patients, no beds available.

Nurses found a corner in a busy corridor where Noor could lie down. The lights flickered, and the generator’s low drone filled the room. There was no privacy, no quiet. Doctors worked quickly, hands steady despite their exhaustion. Noor’s contractions came one after another. Sweat dripped down her face. Finally, a girl was born: her cries faint but still a signal of life. Noor held her daughter close without food, clean clothes, or diapers. The room smelled of fear and hope tangled together, as a new life began amid ruin.

Since the genocide began, official reports estimate that over 3,000 babies have been born in Gaza’s collapsing hospitals. Many arrive too soon, or with health complications caused by malnutrition and inadequate medical care. Many others suffer from disabilities linked to poor prenatal conditions and genocide-related trauma. In the first month of the genocide, United Nations agencies reported that there were about 50,000 pregnant women in Gaza, with more than 180 giving birth every day, and 15 percent of them likely to face complications that require medical care.

Neonatal mortality has risen sharply: Miscarriage rates have tripled and stillbirths surged beyond prewar levels. For the first half of 2025, the U.N. Population Fund reported that among 17,000 births, 20 newborns died within 24 hours, and 33 percent of babies — 5,560 infants — were premature, underweight, or required NICU care. These figures are not just statistics; they are a record of lives that began in crisis.

Birth in Gaza often means sharing incubators, giving birth without anesthesia during power outages, and risking infection because water and sanitation systems are destroyed.

And clothes? Even before the genocide, baby clothes were expensive. Now they’re nearly impossible to find. If you’re lucky, you might come across a scrap of fabric shaped like clothing — but it’s rough, stiff, and anything but comfortable on a newborn’s skin.

Tasneem had hoped, in those early days, that a ceasefire might come before her son arrived. In her final weeks of pregnancy, she held onto the idea that she would give birth in normal conditions — at home surrounded by family, rather than rubble. But the days passed, the bombing grew heavier, and that hope was crushed.

With the support of her family, Dana is growing strong. “She is healthy and happy, thanks to our care and attention,” her mother says. The early hardships have left their mark; subtle signs in her development that remind the family of the struggle before her birth. But the family remains steadfast and says they make sure Dana has milk, diapers, and everything she needs.

None of these mothers had what they needed. What they did have was determination: stubborn, unbreakable, quietly defiant. Each of them carried a life inside them while the world fell apart around them. Each gave birth with explosions in the background, fear in their lungs, and courage in their hands.

To be pregnant in Gaza today is to give life with death knocking at the door.

To be pregnant in Gaza today is to give life with death knocking at the door. It is to feel your baby kick while warplanes circle overhead. It is to count the seconds between explosions and pray the next one doesn’t find you. It is to bring life into a world that feels like it’s ending — and to do it anyway.

In Gaza, where the Israeli government is explicitly seeking to eliminate the existence of Palestinian people, the birth of every child is an act of resistance. These women, sustaining life amid bombs and shortages, rewrite the meaning of courage and resilience. Their strength is not demonstrated in grand speeches or headlines, but in the small moments: steady hands breastfeeding a hungry baby, a newborn’s fragile cry cutting through the sound of bombardment, a family’s silent promise to protect life. They carry the future in their arms, embodying the determination of a people who refuse to disappear.

Despite the violence, the hunger, and the fear, life continues — because in Gaza, to live is to resist.

IT’S EVEN WORSE THAN WE THOUGHT.

What we’re seeing right now from Donald Trump is a full-on authoritarian takeover of the U.S. government.

This is not hyperbole.

Court orders are being ignored. MAGA loyalists have been put in charge of the military and federal law enforcement agencies. The Department of Government Efficiency has stripped Congress of its power of the purse. News outlets that challenge Trump have been banished or put under investigation.

Yet far too many are still covering Trump’s assault on democracy like politics as usual, with flattering headlines describing Trump as “unconventional,” “testing the boundaries,” and “aggressively flexing power.”

The Intercept has long covered authoritarian governments, billionaire oligarchs, and backsliding democracies around the world. We understand the challenge we face in Trump and the vital importance of press freedom in defending democracy.